An ethnographical map of Great Bear Lake

This text provides a variety of ethnographic details on Athapaskan Indigenous groups in northwestern Canada and Alaska (primarily focused on classification, naming, and subdivisions), as well as some geographic description of the regions in which they live. It is included in a larger volume about population change, diversity, practices, and economy across North American Indigenous peoples.

From Abstract:

In the year 1928, I was commissioned as ethnologist by the National Museum of Canada to conduct a study of the Indians of the Great Bear Lake region in the Northwest Territories. I had conceived the project as the first in a series of studies of the Athapaskan-speaking peoples of the interior of northwest Canada and Alaska. On July 1, 1928, I reached Fort Norman (91 — numbers refer to the maps Figures 1 and 2) on the Mackenzie River, and the Fishery (4) at Great Bear Lake on July 23.

Access this Resource:

DOI: 10.2307/j.ctv16t2p.6

Access this resource through your institution on JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv16t2p

Osgood, Cornelius. “An ethnographical map of Great Bear Lake.” In Proceedings: Northern Athapaskan Conference, 1971 volume 2, edited by Annette McFadyen Clark, 516-544. Ottawa: National Museum of Man Mercury Series, Ethnology Service Paper 27, 1975.

Traits of Hare Indian culture: Some Remarks on Åke Hultkrantz's Article: The Hare Indians: Notes on their Traditional Culture and Religion, Past and Present

Broch’s paper engages with the work of another anthropologist, Åke Hultkrantz, and disputes the plausibility of drawing generalizations about Fort Good Hope based on one informant. Broch contends that Hultkrantz’s informant has lived outside of the community for a long time, and only gave partial information about economy, religion, and other features of Fort Good Hope life.

Hultkrantz's original paper is also included in this catalogue.

*The author's name is either spelled Broch or Brock depending on the source journal.

Access this Resource:

Preview the article on Taylor and Francis online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.1974.9981086

Broch, Harald. “Traits of Hare Indian culture: Some Remarks on Åke Hultkrantz's Article: The Hare Indians: Notes on their Traditional Culture and Religion, Past and Present.” Ethnos 39: no. 1-4 (1974): 156-169.

A Note on the Hare Indian Color Terms Based on Brent Berlin and Paul Kay: Basic Color Terms. Their Universality and Evolution

Working in Fort Good Hope in the 1972-1973, Harald Broch interviewed Addy Tobac, Lucy Jackson, Georgina Tobac, and Pasanne Manuel. These informants provided him with a list of colour terms:

white, dεkɂal̨ε

black, dεsεn

red, dεdεlε

yellow, dεfↄ

green, ætʒ

blue, dεtłɂε

pınk, tsε

brown, dεsεn dεfↄ

[*note: the author’s spellings have simply been transcribed as written here]

Broch finds from his informants that red may be related to blood, and that pink, tsǝ, is also a word for sprucegum (which turns dark pink when chewed). Green also means grass, leaves, cabbage, and flowers. Blue, white, and black have no other meanings.

Access this Resource:

Read the full text on JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30029410

Broch, Harald. “A Note on the Hare Indian Color Terms Based on Brent Berlin and Paul Kay: Basic Color Terms, Their University and Evolution.” Anthropological Linguistics 16, no. 5 (1974): 192-196.

On methods in Hare Indian ethnology—a rejoinder

This paper by Hultkrantz engages with Harald Beyer Broch's 1974 criticism of the author's previous work on Hare peoples. The two anthropologists pursue a methodological debate about the merits of social anthropology and in depth interviews.

Broch's original paper has its own catalogue page.

Hultkrantz's first paper in the conversation is also held in this catalogue.

Access this Resource:

Preview the text from Taylor & Francis online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.1974.9981087

Hultkrantz, Åke. “On methods in Hare Indian ethnology—a rejoinder.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 39, 1-4 (1974): 170-178.

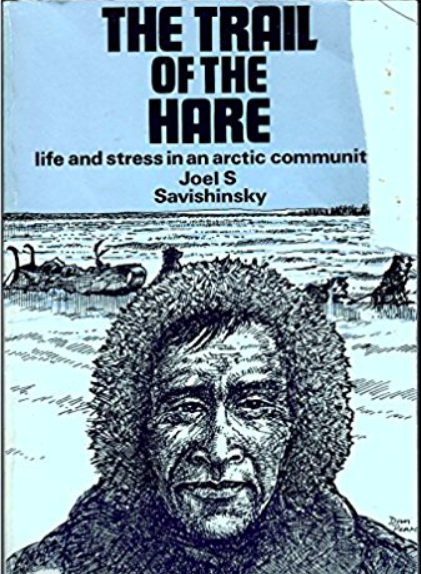

The Trail of the Hare: Life and Stress in an Arctic Community

In The Trail of the Hare, Savishinsky discusses mobility and change in Hare groups, in light of animal rights, environmental concerns, and settler-Indigenous relations.

Description:

Anthropological study of a community of Hare Indians or Kawchottine Indians, Mackenzie District by Colville Lake, N.W.T., based on the author's field work in 1967-68 and 1971.

Access this Resource:

ISBN: 9780677041452

Savishinsky, Joel S. The trail of the hare: Life and stress in an Arctic community. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1974.

Preview the Second Edition on Google Books:

Great Bear Lake Indians: A historical demography and human ecology. Parts 1 & 2.

Morris’ work focuses on Fort Franklin (now Délı̨nę) in the Sahtú region. She splits the results of her research and thesis fieldwork into two primary historical segments (pre and post European contact). Her emphasis is primarily on population, human ecology and geography, and trends in seasonality, subsistence, migration, and other elements of history and social organization.

Access this Resource:

While Morris' two articles are available only as physical documents in several University libraries, a digital copy of the thesis they are based on is online from the University of Saskatchewan: http://hdl.handle.net/10388/etd-07032012-110232

Morris, Margaret W. “Great Bear Lake Indians: A historical demography and human ecology. Part 1: The situation prior to European contact.” Musk-Ox 11 (1972): 3-27.

"Part 2. The situation after European contact.” Musk-Ox 12 (1973): 58-80.

The Hare Indians: notes on their traditional culture and religion, past and present

Hultkrantz recounts an interview with a young man from Fort Good Hope, by the name of “Little Fox,” in the context of historical ethnographic literature. He concludes that the youth of Fort Good Hope are experiencing a resurgence of traditional values and attempting to preserve these where possible.

A response to this article and ensuing academic debate is described elsewhere in this catalogue.

Access this Resource:

Preview the article on Taylor and Francis online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.1973.9981071

Hultkrantz, Åke. “The Hare Indians: notes on their traditional culture and religion, past and present.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 38, 1-4 (1973): 113-152.

Great Bear Lake Indians: A Historical Demography and Human Ecology

Morris’ work focuses on Fort Franklin (now Délı̨nę) in the Sahtú region. Her paper gives an overview of “the changes in human ecology and demography of the Indians of Great Bear Lake from just prior to European contact to the late 1800’s,” (3) with an emphasis on population geography, i.e., the population traits and 'geographic personality’ of places. Her overview includes some valuable historic maps and climate records, along with descriptions of hunting practices, seasonal migration, subsistence, and traditional clothing and cooking. She also provides population estimates from the 19th and 20th centuries for the Great Bear Lake and Fort Good Hope regions.

Abstract:

Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories is the largest lake located entirely within the bounds of Canada. Today there are two small settlements along its shores: the small mining town of Port Radium on McTavish Arm inhabited by non-Indians, and the small Indian settlement of Fort Franklin on Keith Arm. This study is concerned with the Indians of Fort Franklin and district. Fort Franklin is located four miles from where Bear River begins to flow down to the Mackenzie River. It is approximately 90 miles from Fort Norman, the closest community, 120 miles from Norman Wells, and about 400 miles from either Yellowknife or Inuvik (Fig. 1). Its inhabitants in July 1969 comprised 368 Indians (339 Treaty, 29 non-Treaty) and 37 transient whites, mainly government, church or trading officials (Pers. comm. Fr. Denis, 1969). Most of the Indians are fur trappers who live in the "bush" around the lake for three to four months every winter setting up and operating their trap-lines. Their income is supplemented by a spring beaver hunt, by guiding at the tourist fishing lodges located around the lake, or by working with the transportation companies during the summer months. A few are employed either part or full time with the government or Hudson's Bay Company. The Great Bear Co-operative provides an outlet for local handicraft. Social welfare and other government allowances form an increasing proportion of the total income (Pers. comm. W. English, Area Administrator, 1969). Since the erection of about eighteen log houses in the early 1900's, Fort Franklin has had a number of Indians residing in the settlement on a year round basis. With the discovery of pitchblende, silver, and other minerals at Port Radium and petroleum at Norman Wells in the 1920's, Great Bear Lake and River became important as a commercial transportation route. Oil, food, and equipment were barged upstream, and silver-copper concentrates downstream to Fort McMurray, and then by rail to the smelter at Tacoma, Washington. Later, radium was sent to Port Hope, Ontario, for refining at Eldorado (Eldorado, 1967, pp. 18-21). Following upon the establishment of a permanent Roman Catholic Mission, Federal Day School, and Hudson's Bay Company post in 1949-50, the Indians settled in Fort Franklin, and since that time, their numbers have more than doubled. Prior to 1900, these Indians were quasi-nomadic and lived in camps around Great Bear Lake. Once, their forefathers had been nomadic hunters, pursuing the migratory Barren Ground caribou, and subsisting on fish, hares, and other animals in abundant supply. But during the century and a half of European contact these Indians underwent many changes. Most significantly, they decreased in number and gradually became settlement-orientated. The old life of the "bush" and caribou was forever gone.

Access this Resource:

A digital copy of this thesis is available online from the University of Saskatchewan: http://hdl.handle.net/10388/etd-07032012-110232

Morris, Miggs. Great Bear Lake Indians: A Historical Demography and Human Ecology. Master’s Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1972.

Ice and Travel among the Fort Norman Slave: Folk Taxonomies and Cultural Rules

Basso applies sociolinguistic theory to ethnographic data in order to derive a set of 'Slave’ rules for crossing or avoiding ice. He highlights the importance of describing not just a structurally coherent set of internal cultural rules, but also the importance of effectively contextualizing them and their use.

Abstract:

Through the use of data collected among Slave Indians living in northern Canada, this paper explores a problem in ethnographic methodology: how to describe cultural rules such that contextual restrictions which operate upon thme are identified and made explicit. Following a discussion of some of the ways in which the aims and assumptions of current sociolinguistic theory can be applied to this problem, a formal model is presented of Slave rules for travelling on the ice of frozen lakes and rivers. This model, which specifies the conditions under which a Salve hunter can be expected to cross an expanse of ice or avoid it, reveals the sensitivity of normative rules to variation in contextual features and illustrates both the value and feasibility of incorporating these features into ethnographic accounts.

Access this Resource:

Read the full text on JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4166668

Basso, Keith H. “Ice and Travel among the Fort Norman Slave: Folk Taxonomies and Cultural Rules.” Language in Society 1, no. 01 (1972): 31–49.

Kinship and the expression of values in an Athabascan bush community

This text is based on mid-20th century ethnographic work and focuses on social relationships in Indigenous northwestern Canada.

Read more about Savishinsky's work and preview his book, The Trail of the Hare.

Access this Resource:

Search for this article in your local University library.

ISSN:0008-5340

Savishinsky, Joel S. “Kinship and the expression of values in an Athabascan bush community.” In Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 2, no. 1, edited by Regna Darnell (1970): 31-59.

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: