North Slavey Terminology and Concepts Related to Renewable Resources: An Interim Report, Tı̨ch’ádı Hek’éyedıts’ǝ́dı gha Xǝdǝ Hé Goghǫ Dáts’enıwę Ghǫ Ɂedátl’e.

Project Coordinator: Helena Laraque. Cover Illustration: John Williamson.

The authors describe the process and constraints involved in gathering and verifying Dene Kedǝ terminology related to renewable resources. The rest of the document includes lists of terms that have been translated, will be translated, and participants.

Access this Resource:

A physical copy of this resources is held at the University of Aberta Library in the Circumpolar Collection (Cameron), call number PM 2365 M37 1994. Last accessed July 2017.

Masuzumi, Barney, Dora Grandjambe, and Petr Cizek [Dene Cultural Institute]. North Slavey Terminology and Concepts Related to Renewable Resources: An Interim Report, Tı̨ch’ádı Hek’éyedıts’ǝ́dı gha Xǝdǝ Hé Goghǫ Dáts’enıwę Ghǫ Ɂedátl’e. Government of the Northwest Territories Department of Renewable Resources: Yellowknife, 1994.

“Together, we can do it!” 2nd Annual Report for the period April 1, 1993, to March 21, 1994

This report reviews completed and outstanding recommendations from the previous year, including the initiative to disseminate information about the Act and the role of the Languages Commissioner to the public. The documents for this purpose were produced in the early-mid 90s and were in all Official Languages; they included bookmarks, brochures, and a summary of rights bestowed by the OLA.

In the reporting period, the office of the languages commissioner dealt with “377 complaints and inquiries, 80% of which are completed” (5) re OLA guidelines and their effective implementation. The Languages Commissioner’s office had to determine what was a valid complaint. E.g., the OLA says service must be provided in an OL when there Is “significant demand,” but metrics for such are not specified. After breaking down some statistics on language use in the territories, as well as OLA complaints and inquiries, Harnum notes that the Federal government funding for OLA implementation was cut by 10% in 1993-4, with further cuts promised.

Access this Resource

This document has been archived by the NWT Department of Education, Culture, and Employment.

Office of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories [Betty Harnum]. “Together, we can do it!” 2nd Annual Report for the period April 1, 1993, to March 21, 1994. Yellowknife, 1994.

Literacy: A Critical Element in the Survival of Aboriginal Languages

Fogwill describes the languages of the Northwest Territories and the demographics at the time of writing, noting that the NWT had the youngest population in Canada and the highest birthrate. The majority of members of the NWT Legislative Assembly and Cabinet were Aboriginal. Fogwill posits three main phases of education in the Northwest Territories: mission (1800s-1950), federal (mid 1940s-1970), and territorial (1967-). In addition, she tracks the discussions contributing to education reform in the NWT, including community testimony and assessments. Fogwill’s key theme is that NWT grade school, at the time of writing, was ill-equipped to provide education that would help a child advance professionally in the north. As such, if a child dropped out of school (and when Fogwill was writing, only 5% of Aboriginal people in Canada graduated grade 12) (s)he would be unprepared both for wage labour and for a traditional lifestyle. Possible solutions such as Dene Kede curriculum were just beginning to be developed/implemented at this time, and had not yet been evaluated.

Access this Resource:

Download the full text of the edited volume on ERIC.

Fogwill, Lynn. “Chapter 16: Literacy: A Critical Element in the Survival of Aboriginal Languages.” In Alpha 94: Literacy and Cultural Development Strategies in Rural Areas, edited by Jean-Paul Hautecouer. 229-248. Toronto: Culture Concepts Publishers, 1994.

First Annual Report of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories for the Year 1992-1993

This extensive report covers a large amount of important material. In its preface, Harnum comments on the creation of the office of the Languages Commissioner as a linguistic ombudsperson during the 1990 amendments to the 1984 Official Languages Act. These same amendments gave equal official status to all of the eight named languages, including Indigenous languages.

Harnum identifies linguistic subgroups within each official language (in North Slavey, she comments that “native speakers can identify as many as six or seven sub-groups.” (14)). In addition, at the time of writing Statistics Canada only differentiated between 'Hare’ (Colville Lake region) and 'Slavey,’ but did not report on other dialects or the differences between North and South Slavey. This being said, Harnum pulls from Statistics Canada figures to discuss language shift and its acceleration in Dene languages. The question on “ability to converse” was only added to the census in 1991; this question allowed researchers to track self-reported second language learning.

With regard to literacy, Harnum simply comments on the dearth of good research. She comments that the NWT Literacy Council has been one of the few to do a study of this kind, but it works with a small sample only. Despite this dearth, Statistics Canada has some useful 1991 data that shows that of all Aboriginal people who could read/write in an Indigenous language in the NWT, 5.7% of them could read Slavey, and 3.8% could write Slavey. This data does not capture whether or not people are referring to syllabics or roman orthography.

Access this Resource:

This document is archived in the NWT Department of Education, Culture, and Employment.

Office of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories [Betty Harnum]. First Annual Report of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories for the Year 1992-1993. Yellowknife NT, 1993.

North Slavey Terminology Lists, Interpreter/Translator Program

Students (full time and part time) of the Interpreter/Translator program at Arctic College, Thebacha campus, developed this terminology between 1990 and 1993. The instructor was Marlene Semsch. Most of the words in the publication are included if they meet the standard of having been agreed upon by a group of two or three students.

The key vocabulary topics include: Language Issues, Social Issues, Environment, Education, Medical, Rules of Order, and Land Claims. Some examples include:

Appendix, “ɂenı́tłe golódátłe”

Bursarıes (money to go to school) “sǫ́baa bet’a enı̨htłé kǫ́ ɂats’etı̨”

Agenda, “ayı goghǫ gots’ude”

Meetıng, “gots’ede”

Unanımous consent, “dene areyǫné heɂę enakı̨t’éle”

Access this Resource:

Semsch, Marlene and Students. No title. Interpreter/Translator Program North Slavey Terminology Lists. Fort Smith: Arctic College, Thebacha Campus, 1993.

A Report on the Arctic College Interpreter-Translators Program

This article provides a historical overview of interpreter/translator (I/T) training in the Northwest Territories, focusing on Arctic College programs at Thebacha Campus (Fort Smith) as compared with Nunatta Campus (Iqaluit). The Northwest Territories Department of Information formed the Interpreter Corps in 1979, and launched I/T training at the same time. The same department became Culture and Communications a few years later, and the program was renamed “the Language Bureau,” which in 1993 provided on the job training for Dene or Inuktitut-English employees.

In 1987, a one-year I/T certificate program was developed at Arctic College by Marilyn Phillips and the Language Bureau. By 1993, a second year diploma was in place. At the time of this paper’s writing, it was offered in two locations: Thebacha (for Dene students) and Nunatta (for Inuit Students). To qualify for the program, students had to be orally fluent in Dene and have completed Grade 10. They often learn to write in their language in the program, “since a standardized system of writing Anthapaskan languages [had] only recently been accepted” (96). The languages taught were “Gwich’in, North Slavey, South Slavey, Dogrib, and Chipewyan,” (96) and the Dene classes were “Professional Development, Northern Studies, Keyboarding, Communications, Speech and Performance, Listening Labs, English Writing Lab, Dene literacy, Linguistics… Translation Methods, Interpreting Methods, Simultaneous and Consecutive Interpreting, and two Practica” (97).

One major challenge this program encountered was evaluation. No Dene native speaker had completed a degree in interpreting or translating or written a “CTIC” exam. Most elders were unilingual, and thus unable to evaluate simultaneous interpretation (as judged by the program). A second challenge was enrolment, which was endemically low, in part because potential students could not find housing for their families near each campus. Finally, I/T services were in such high demand that translators often did not need formal training to acquire a job.

Abstract:

This report briefly outlines the historical developments of interpreter I translator training in the Northwest Territories. It describes the origins of the present Arctic College I IT programs at the Thebacha Campus in Fort Smith and Nunatta Campus in Iqaluit and describes their similarities and differences. It outlines admission requirements and course offerings and discusses some of the challenges faced in training aboriginal translators and interpreters.

Access this Resource:

The full text of this article can be downloaded from erudit.

Semsch, Marlene. “A Report on the Arctic College Interpreter-Translators Program.” Meta 38, no. 1 (1993): 96-91.

Language Initiatives

The primary focus of this text is the history of writing systems for Dene languages. Following syllabics, Roman orthography alphabets were created in the 1950s and 1960s. In the early-mid 1970s, the Government of the Northwest Territories began running Teacher Education Program literacy workshops, and as students became skilled in literacy they were hired as language specialists to conduct further literacy workshops and courses. A paucity of reading materials in Aboriginal languages, in addition to numerous other challenges, made it very difficult to teach these classes.

Abstract:

The Dene (Indian) languages of the MacKenzie Valley of the Northwest Territories are Chipewan, Dogrib, Gwich'in and Slavey. These people did not traditionally write their languages, but in recent years linguists have produced alphabets that accurately represent the sounds of these languages. Since the 1970's the Government of the Northwest Territories, via the Department of Education and the Teacher Education Program has been sponsoring workshops and courses designed to enable many Dene to read and write in their languages, and to become language specialists qualified to teach literacy to others. These courses are not structured for totally non-literate people, but for students orally fluent in their native tongue, who are already literate in English, having already been through the English-medium primary and secondary school systems. The courses employ techniques which engender skills in syllable and sound discrimination. When a student has mastered these skills he I she is able to read and write accurately in the native language and needs only time and practice to develop fluency in literacy. There are currently a number of Dene who have achieved such fluency.

Access this Resource:

The full text of this article can be downloaded from Erudit.

Howard, Philip G. “Language Initiatives.” Meta 38, no. 1 (1993): 92-95.

Terminological Difficulties in Dene Language Interpretation and Translation

Betty Harnum’s paper identifies the challenges faced by Dene language interpreters due to a lack of specialization and demand for a wide range of services. Dene Interpreters and Translators (I/Ts) have had to quickly adapt their languages to new concepts, items, and ideas. The author outlines the methods commonly used by I/Ts to create new nomenclature, specifically:

“a) borrowing a word from the source language, with various phonological changes (sound-changes) in order to adapt the pronunciation of the word to the available sound inventory of the target language;

b) creating a new lexical item by describing some feature(s) of the item, idea or concept; and

c) expanding or shifting the meaning of an existing word or phrase.” (105)

Terminological variation and inconsistency often creates problems for Dene language interpreters who should have more opportunities for training and terminology development.

Abstract:

In the Northwest Territories, there are daily demands for interpreting and translating in all the Dene languages. The people who perform this role rarely have the opportunity to specialize in any specific field, so they must try to develop an understanding of as many subjects as they can. This paper highlights some of the inter-lingual difficulties faced by the interpreters, along with a brief explanation of the methods used to develop new terminology in the Dene languages. It is demonstrated that the methods used in Dene language terminology development are the same as those used in other languages.

Access this Resource:

DOI: 10.7202/003026ar

Access the full text of this article from Érudit.

Harnum, Betty. “Terminological Difficulties in Dene Language Interpretation and Translation.” Meta 38, no. 1 (1993): 104-106.

Report of the Dene Standardization Project

Sponsored by the Department of Culture and Communication and the Department of Education. North Slavery Working Committee: Sarah Doctor, Keren Rice, Paul Andrew, Dora Grandjambe, Jane Vandermeer, Judi Tutcho, Lucy Ann Yakeleya, Ron Cleary, and Agnes Naedzo.

In the 1970s, the Athapaskan Languages Steering Committee piloted the idea of standardization, and, in 1985, the GNWT created a Task Force on Aboriginal Languages which recommended the same. In 1987 the Dene Standardization Project was born, with the goal to make decisions regarding Dene orthographies, publish reference materials, support native language specialists and teachers to learn new orthographies, and other measures. Regional standardization was to be based on the speech of Elders.

Dene Kedǝ or North Slavey language had its own, unique considerations (from the "North Slavey Technical Report", p. 46)

• Dene Kedǝ at this time was thought to consist of “three major dialects, Rádeyı̨lı̨ ,Délı̨ne, and Tulı́t’a. The community of Tulı́t’a has two major dialects within it…. [one] very similar to that of Délı̨nę, which can be called the kw dialect, while others use the dialect that is labeled Tulı́t’a in this report, or the p dialect. Speakers from Rádeyı̨lı̨ and K’áhbamı̨túé use the f dialect.” (46)

• These dialects vary in emphasis, vocabulary, tone, etc.

• There are intergenerational and, possibly, gendered differences in speech.

The Standardization team also generated numerous recommendations for implementing standardized orthographies. These included using only standardized writing in GNWTpublications, holding public awareness and literacy campaigns, publishing more materials, and supporting language teachers to learn the new systems.

Access this Resource:

Contact the NWT Archives to obtain permission to access records from the Standardization project. See Accession no. G-2003-01. In addition, a paper on the Standardization project with similar content is available open access from ERIC.

Government of the Northwest Territories. Report of the Dene Standardization Project. Yellowknife, 1990.

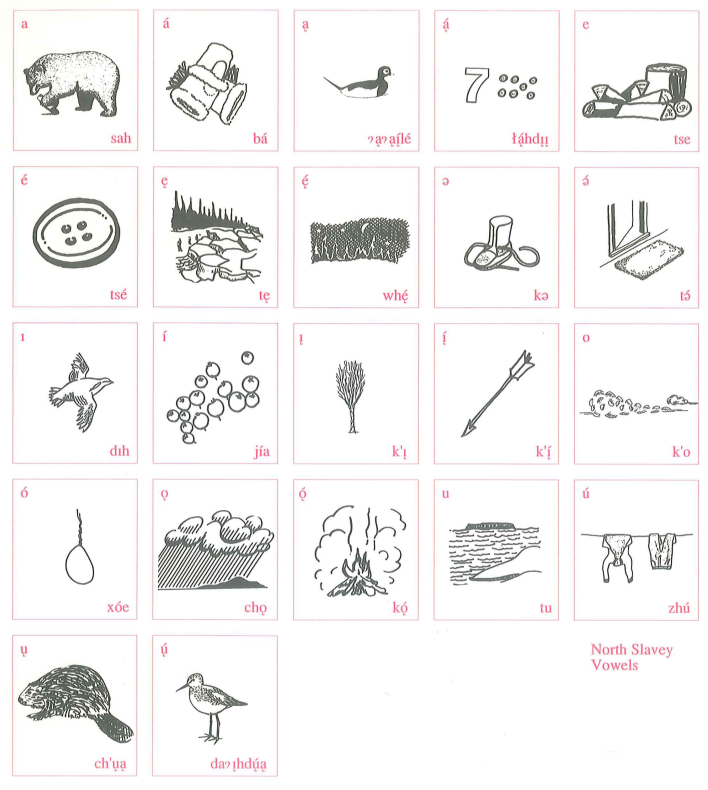

North Slavey Vowels and Dipthongs Chart

This is a one page chart of Dene vowel sounds and pictures of what they represent. It was published with the NWT Department of Education, Culture, and Employment.

Preview the chart below:

Access this Resource:

North Slavey Vowels and Dipthongs Chart. Northwest Territories Department of Educatıon, Culture, and Communications, 1990.

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: