Fur Trade

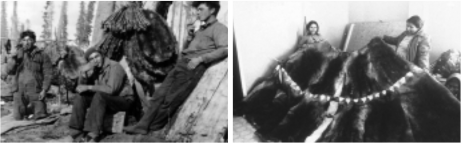

The people of the Sahtu were introduced to a fur trade economy by way of traditional trade routes with the Dene Suåline (Chipewyan) people, long before European traders made their way to the area. The northern fur trade era with the English and French traders began in 1670. Under a Royal Charter, the Hudson Bay Company was given ownership of the lands drained by the Hudson Bay. Over the next 100 years, trading centred in this region known as Rupert’s Land. It was not until trade routes were established further north and west that traders looked to the Sahtu.

At the turn of the 18th century, fur trading posts under the North West Company were established in the Sahtu after Alexander Mackenzie’s exploration of the Deh Cho River. The North West Company established a post in Deline (Fort Franklin) in 1799, in Tulita (Fort Norman) and in the vicinity of Fort Good Hope in 1804-1805. In 1821, the North West Company joined the Hudson’s Bay Company. A century of relationships developed through the fur trade gave rise to the Métis Nation, a distinct people that brought together Dene and European cultures.

In the early days of the fur trade, the Dene would seldom trap a locality out. Subsisting out on the land, they would move camp often in search of game and would consequently trap lightly over a large area.

But fur was a lucrative commodity for European traders, and the trade rapidly expanded, exerting new pressures on fur-bearing animal populations. Early on, ships that delivered £650 worth of trade goods were returning to England with £19,000 worth of furs. Europeans increasingly found it profitable to enter the trade as trappers. In contrast to their nomadic Dene counterparts, European trappers brought most of their own provisions, established themselves in a chosen locality, built headquarters with small buildings and devoted most of their time to trapping to supply the market. In a few years, nearby fur-bearing populations would be exhausted, forcing them to seek new trapping areas.

As the 20th century dawned, trapping had become an established modern, market-driven activity. However, over-trapping and over-hunting were causing severe shortages of the wildlife that had been the source of survival for the Dene and Métis peoples. The tensions of those times are evoked in Dene bushman stories, which are said to be a response to the fearsome white strangers that had entered the wilderness.

WHEN THE BUSHMAN CAME TO TOWN

By Corey Chinna, Gr 7-12, Fort Good Hope

(Originally printed in the Mackenzie Valley Viewer, February 2001)

I was just coming from my friend’s house when I saw some kids riding around on skidoos. So I ran home to get my skidoo. I grabbed the skidoo from my house, and took off to follow the other kids. By the time I caught up with them, it was already dark. I just followed the skidoo in front of me.

Then I heard a weird noise coming from the engine. So I stopped to check it out. It didn’t look like anything was wrong. I kicked the engine, and it went back to normal. I jumped back on and took off again.

All the kids were gone already, except one. So I followed him. He slowed down and stopped. I asked him if he knew where the other kids went. He didn’t answer. I looked at his clothes. They were all hair! I remember my granny telling me a bushman was wandering around.

Then he stood up. He was about seven feet high, and hairy, too. He started grumbling like he was talking. I took off around a corner. I thought I’d lost him, so I said, “Whooo!” Then he jumped out of the bushes and covered my eyes so I couldn’t see. I crashed into a ditch. When I turned around, he wasn’t there. I went to the road to see if I could see him. I said, “Aah, I guess I’ll go home and tell my dad about the skidoo.”

Then I turned and there he was, towering over me like a giant. He grabbed me and picked me up. Suddenly something came out of nowhere and crushed the bushman. He was out cold. Later, I saw his arm move, so I ran.

He was running after me. I ran onto the river, which it wasn’t very frozen. I kept running, and all of a sudden he fell through the ice. I checked to see if he fell in for sure. Then his big hand came out and grabbed my leg. I pulled out my lighter and burned his hand. Then he went back under. I ran home to warm up.

Mackenzie’s Mistake

On June 3,1789 25 year old fur trader Alexander Mackenzie, led his 12-person crew of French-Canadian voyageurs and Chipewyan guides and their fleet of birchbark canoes into the cold water of Lake Athabasca. He had every reason to believe that the voyage would lead westward to the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

The Pacific quest however was difficult from the outset. Progress on the Slave River, leading north was slow, and dangerous. Unseasonable ice on Great Slave Lake often brought the fragile birchbark canoes to a standstill.

The sagging spirits of the crew lifted when the next great river (Deh Cho) began to carry them westward. Soon the snow-capped wall of the Rocky Mountains in the distance appeared. But when the river itself turned north and parallel to the mountains, at Camsell Bend, the paddlers realized that their quest for the Pacific would be a failure.

On July 16, 6 weeks after their optimistic departure their fears were confirmed: their route had taken them not to the Pacific Ocean, but to the Arctic. Disappointed, Mackenzie and his guides paddled back to Lake Athabasca.

In May of 1793, Mackenzie tried a second time. This time he headed west from Athabasca, following the Peace River to the continental divide and reached the headwaters of the Fraser River which flows into the Pacific at present-day Vancouver.

His guides knowing the river's dangerous reputation advised Mackenzie against attempting to descend it. Instead, the explorer descended the Bella Coola River, becoming the first European to cross North America north of Mexico.

Adapted from Canadian Council for Geographic Education’s “Mackenzie River - Wrong Turn.”

[ Sahtu Atlas Table of Contents ]

[ Next Section ]

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: