Recognizing Traditional Environmental Knowledge

This paper goes over an interview with Matha Johnson, then Research Director of the Dene Cultural Institute (DCI). The conversation touches upon TEK in schools, challenges and opportunities faced by the DCI in its early years, and the future of TEK in resource management.

From Introduction:

"Western science’s failure to recognize traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) was first made obvious to Martha Johnson more than ten years ago when she was working as a high school teacher in Povungnituk, an Inuit community in northern Quebec. She remembered realizing that “as a non-Aboriginal trying to teach science from a Western perspective, it wasn’t working. So I asked myself, “How do the Inuit perceive the environment?” Johnson began experimenting in learning techniques to find ways of tapping the knowledge passed down among the Inuit. In one exercise, she gave students a diagram of the Arctic food chain and asked them to make the links. One practically illiterate boy made the connections without any problems. Later, Johnson pursued a Master’s degree in Environmental Studies and Anthropology at the University of Toronto. Her major paper examined Inuit folk ornithology, comparing Inuit classification of birds to Western groupings. Johnson’s grassroots experience with Aboriginal communities and her formal studies helped her recognize the holistic nature of TEK. “It combines biology, linguistics, social sciences, and other disciplines and connects them in an interdisciplinary way to examine how people perceive their world, live within it and use its resources” she comments. Johnson spoke about traditional environmental knowledge, the reasons behind its growing recognition, and current research in this field during an interview in Ottawa early this year. She is now Research Director of the Dene Cultural Institute in Canada’s Northwest Territories. The Institute works with Dene communities to preserve and promote this Canadian aboriginal group’s culture, through research and education. Much of the Institute’s work has focused on TEK through research and the publication of a book entitled Lore: Capturing Traditional Environmental Knowledge, edited by Johnson. The book was based on papers produced from a 1990 workshop on TEK, organized by the Dene Cultural Institute. IDRC funded the workshop as a cultural exchange between researchers in developing countries and those working in Canadian aboriginal communities. Community-based projects on TEK in the Amazon Rainforest, the African Sahel, the South Pacific and Southeast Asia were represented at the workshop. The Institute also invited aboriginal community members and researchers from northern Canada’s Belcher Islands. Workshop participants discussed the problems of gathering TEK and integrating it with Western Science to improve natural resource management. They also experienced Dene culture through food, music and dance. The participants’ papers, outlining their project’s research methodology, were incorporated in Lore."

Access this Resource:

The full text of this paper is available from the Community Development Library.

Carter, Deborah. “Recognizing Traditional Environmental Knowledge.” Ottawa: International Development Research Centre Reports 21, no. 1 (1993).

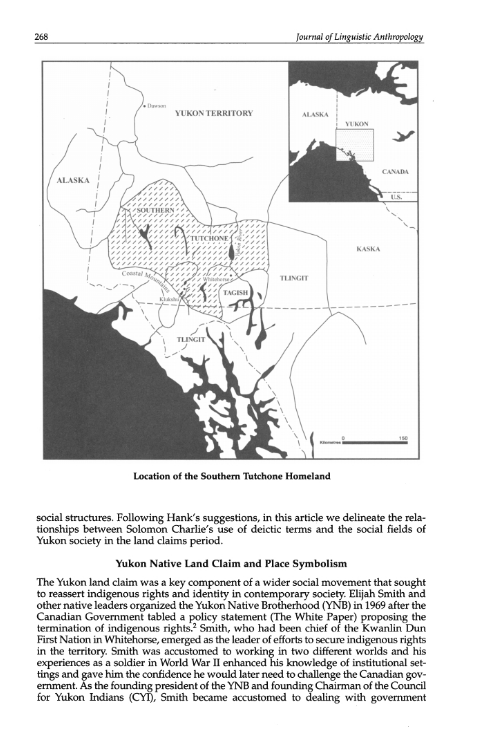

Indigenous Linguistics and Land Claims: The Semiotic Projection of Athabaskan Directionals in Elijah Smith's Radio Work.

The authors discuss a 1985 Southern Tutchone radio broadcast wherein co-performers used deitic spatial terms, placing a listener in relationship to the landscape being discussed, and “spatially evoking the history of the entire region.” (282). The authors contend that the linguistic features of radio performances such as these are linked to social uses and perceptions of place, including land claims and Indigenous rights to land.

Access this Resource:

Moore, Patrick and Daniel Tlen. “Indigenous Linguistics and Land Claims: The Semiotic Projection of Athabaskan Directionals in Elijah Smith's Radio Work.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 17, no. 2 (December 2007): 266-286.

Time and Story in Sahtú Self Government: Intercultural Bureaucracies on Great Bear Lake

Rice’s thesis explores Délı̨nę at the time of transition to self-government (2015). It describes the community’s hopes for self government’s future, the history that lead to its negotiation, the ways in which a legal agreement’s text may diverge from the ideas people hold about it, and the ways in which people are impacted by the new roles created by institutions of governance.

In many ways, Dene Ts’ı̨lı̨ has the power to transform Canadian institutions and laws, as in when Dene SSI board members in Délı̨nę use Dene Kedǝ to change the mood and content of an otherwise sterile meeting, and remind their leaders of their Dene origins. Dene understandings of the Final Self Government Agreement are different than the text itself: its oral life has different power in Délı̨nę than the written document, and opportunities for the FSGA to be a vehicle for Dene Ts’ı̨lı̨ and Dene Kedǝ lie in people’s hopes and plans for the future. In 2015, the mere idea of self-government had generated significant energy and planning around Dene Ts’ı̨lı̨ and Kedǝ preservation and revitalization.

From Abstract: "This thesis explores aspects of self-government in Délı̨nę, NT, Canada, a Sahtú Dene community of approximately 550 people. Délı̨nę’s Final Self Government Agreement (FSGA) was passed by the federal government of Canada in 2015, and the research for this thesis coincided with the beginning of Délı̨nę’s one-year transition into self government. The FSGA follows the Sahtú Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement of 1993, and the region falls within Treaty 11. This thesis’ primary question is: What are the shared stories about the future of self-government that people in Délı̨nę tell? Subsidiary questions and themes that emerged from the research process include: How does the history of the Sahtú region inform contemporary negotiations, agreements, and the stories told about them? How do new roles created by institutions of governance impact the people who hold them? How does the text of a self-government agreement diverge from the ideas that people have about self-government?"

Access this Resource:

This thesis has been made available open access from the University of Alberta here: http://hdl.handle.net/10402/era.43158

Rice, Faun. Time and Story in Sahtú Self Government: Intercultural Bureaucracies on Great Bear Lake. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, 2016.

Belare Wı́le Gots'ę́ Ɂekwę́ - Caribou for All Time: A Délı̨nę Got’ı̨nę Plan of Action

This is a traditional Caribou management plan, approved by Délı̨nę First Nation, Land Corporation and Ɂehdzo Got'ı̨nę. It is the first plan of its kind in Canada. After a formal public hearing, the plan was also approved by the SRRB and subsequently by the GNWT Minister of Environment and Natural Resources.

Access this Resource:

This resources is available elsewhere on the SRRB Website. Or, download the PDF from the attachment at the bottom of this page.

Délı̨nę Ɂekwę́ Working Group. Belare Wı́le Gots’ę́ Ɂekwę́ – Caribou for All Time. Délı̨nę : Délı̨nę Ɂekwę́ Working Group, 2016.

Language, Distance, Democracy: Development Decision Making and Northern communications

The authors examine the relationship between connectivity, communications infrastructure, and democratic expression and civic participation. In an analysis of the Mackenzie Valley pipeline inquiry and the 2012-2013 Nunavut May River iron ore hearings, the Dalseg and Abele contend that communications technology is essential, but only functional given certain social and organizational conditions. These conditions include: local institutions for citizen mobilization, Indigenous language use, funding, and receptive public institutions.

The authors define a Northern problem they call “knowledge isolation,” which captures the difficulties of sharing essential information across Northern communities quickly, along with a dearth of opportunities to discuss collective decisions. They then turn to a history of northern communications technology, beginning after the Second World War. The introduction of radio in the 1950s through 1970s played an important role in Indigenous communities’ ability to mobilize politically and share knowledge. Television also expanded quickly after the Anik satellite permitted broadcasts to and from the north in 1973.

The Berger Inquiry was broadcast both on television and over CBC radio, along with topical bi-weekly documentaries on Our Native Land. Two Indigenous language broadcasters worked with CBC Northern Service and filed daily reports in seven Indigenous languages: Chipewyan, Dogrib, North and South Slavey, Gwich’in, and Inuktitut. Louie Blondin translated North and South Slavey. These translations were essential to the inquiry’s success, as they ensured that all communities understood the issues at play, and could hear their own perspectives echoed in other places.

From Abstract:

In a country as large as Canada, connectivity—whether by road, rail, radio, or the Internet—plays an important role in economic growth, political and social development, and civic engagement. The importance of communications infrastructure especially is evident in the northern two-thirds of Canada, where radio, television, and the Internet have been instruments of democratic expression and civic participation. As pressures for resource extraction mount, northern communities must respond to economic, social, and political challenges from a position of geographical and, more significantly, “knowledge” isolation. Northern community residents need effective, community-led channels of communication. Addressing these needs will require both social and technological innovation—which can, fortunately, proceed from an existing base of experience and community expertise. In this article, we analyze two moments in northern public policy discourse in which new communications media played a pivotal role in advancing democratic dialogue in northern Canada: the 1975-7 Mackenzie Valley pipeline inquiry, and the 2012-3 hearings into the Mary River iron ore project in Nunavut. Our goal is to advance understanding of the purposeful use of communications infrastructure to support the development of local understanding, citizen engagement, and opportunities for effective community participation in development decisions. We find that technological capacity is foundational, but effective only under specific social and organizational conditions, which include the existence of appropriate institutions at the local level for citizen mobilization and response, dominance of Indigenous language use by northern citizens, appropriate levels of funding, and receptive public institutions to and through which northern citizens can speak.

Access this Resource:

Download this paper for free from The Northern Review: http://journals.sfu.ca/nr/index.php/nr/article/view/473/yukoncollege.yk.ca/review

Kennedy Dalseg, Sheena, and Frances Abele. “Language, Distance, Democracy: Development Decision Making and Northern communications.” The Northern Review 41 (2015): 207-240.

Gúlú Agot'ı T'á Kǝ Gotsúhɂa Gha (Learning about Changes): Rethinking Indigenous Social Economy in Délınę, Northwest Territories

This paper came out of the Social Economy Research Network of Northern Canada (SERNNoCa) established 2006. The network encouraged research in communities such as Délı̨nę, where a project on social economy was conducted from 2009 to 2011, co-occurring with projects on the Délı̨nę Knowledge Centre and Port Radium. The authors unpack Indigenous social economy in Délı̨nę as a case study of intersecting models: “non-commodified kinship based subsistence production and sharing…, wage labour, government subsidies, commodified goods and services, and imported social economy institutions” (254).

They also question the value of functionalist analyses of social economies as based around economic needs, when Indigenous communities may define their own goals and aspirations that do not fit into typical models. Using Dene Ts’ı̨lı̨ (being Dene) as a conceptual starting point, the authors analyze social economy using language and oral traditions. Délı̨nę community members identified four key research needs: caribou knowledge and stewardship, audio documentation of Sahtú spirituality and well-being, climate change and community responses, and youth knowledge.

Access this Resource:

Simmons, Deborah, Walter Bayha, Ingeborg Fink, Sarah Gordon, Keren Rice, and Doris Taneton. “Gúlú Agot’ı T’á Kǝ Gotsúhɂa Gha (Learning about Changes): Rethinking Indigenous Social Economy in Délı̨nę, Northwest Territories.” In Northern Communities Working Together: The Social Economy of Canada’s North, edited by Chris Southcott, 253-274. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Read the Google Book Preview

Where the Rivers Meet: Pipelines, Participatory Resource Management, and Aboriginal-State Relations In the Northwest Territories

Excerpt from Summary:

Oil and gas companies now recognize that industrial projects in the Canadian North can only succeed if Aboriginal communities are involved in the assessment of project impacts. Are Aboriginal concerns appropriately addressed through current consultation and participatory processes? Or is the very act of participation used as a means to legitimize project approvals? Where the Rivers Meet is an ethnographic account of Sahtu Dene involvement in the environmental assessment of the Mackenzie Gas Project, a massive pipeline that, if completed, would transport gas from the western subarctic to Alberta, and would have unprecedented effects on Aboriginal communities in the North. Carly A. Dokis reveals that while there has been some progress in establishing avenues for Dene participation in decision-making, the structure of participatory and consultation processes fails to meet expectations of local people by requiring them to participate in ways that are incommensurable with their experiential knowledge and understandings of the environment. Ultimately, Dokis finds that despite Aboriginal involvement, the evaluation of such projects remains rooted in non-local beliefs about the nature of the environment, the commodification of land, and the inevitability of a hydrocarbon-based economy.

Access this Resource:

Dokis, Carly A. Where the Rivers Meet: Pipelines, Participatory Resource Management, and Aboriginal-State Relations In the Northwest Territories. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2015.

Read the Google Book Preview

Best of Both Worlds: Sahtú Gonę̨̨́nę́ T’áadets’enıt̨ǫ – Depending on the Land in the Sahtú Region

Best of Both Worlds was a project sponsored by the SRRB that lead to the development of an action plan for a traditional economy in the Sahtú Region.

The Best of Both Worlds project is described in greater depth on its own section of the SRRB website, where the full PDF is also available.

Access this Resource:

Harnum, Betty, Joseph Hanlon, Tee Lim, Jane Modeste, Deborah Simmons, and Andrew Spring with The Pembina Institute. Best of Both Worlds: Sahtú Gonę́nę́ T’áadets’enı̨tǫ, Depending on the Land in the Sahtú Region. Tulıt’a: Ɂehdzo Got’ı̨nę Gots’ę́ Nákedı, Sahtú Renewable Resources Board, 2014.

Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization

The authors introduce a special issue of Decolonization on the topic of land-based education. They frame the articles to follow with the premise that separating Indigenous peoples from land is a fundamental quality of colonization; and, as such, land-based education is an essential component of decolonization.

From Abstract:

This paper introduces the special issue of Decolonization on land-based education. We begin with the premise that, if colonization is fundamentally about dispossessing Indigenous peoples from land, decolonization must involve forms of education that reconnect Indigenous peoples to land and the social relations, knowledges and languages that arise from the land. An important aspect of each article is then highlighted, as we explore the complexities and nuances of Indigenous land-based education in different contexts, places and methods. We close with some reflections on issues that we believe deserve further attention and research in regards to land-based education, including gender, spirituality, intersectional decolonization approaches, and sources of funding for land-based education initiatives.

Access this Article:

The full PDF of this article is available from Decolonization online.

Wildcat, Matthew, Mandee McDonald, Stephanie Irlbacher-Fox, and Glen Coulthard. “Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, no. 3 (2014): I-XV.

Dechinta Bush University: Mobilizing a knowledge economy of reciprocity, resurgence and decolonization

Ballantyne uses Dechinta, 'Bush University,’ as an example of a decolonizing space, and comments on the responsibilities of settlers interested in decolonization theory. The author begins by addressing her own settler roots, then turning to the history of oil development in the Northwest Territories. She discusses the Berger inquiry, the land claim processes, and the diamond boom, and argues that the sense of inevitability with which resource exploitation is treated is counterintuitive to decolonizing efforts. Inevitability is inculcated in the early space of youth education, and Ballantyne reflects on experiences working in Fort Good Hope that helped her realize that a contextualized, land-based, collaboration-based pedagogy could be far more transformative for youth than classroom-based education.

From Abstract:

This article explores Dechinta Bush University as an Indigenous place-based movement that contributes to personal and collective transformation through mobilizing land-based knowledge and learning within a comprehensive strategy of resistance to settler capital. Through the production of a knowledge economy intervention, the pedagogical and political strategies of Dechinta are explored as a proven example of multi-scalar transformational decolonization that has far-reaching personal, collective, institutional, political and economic impacts. Through a detailed exploration of the five-year process of collective imagining, mobilizing and operating Dechinta Bush University, this article gives critical insights into closing the gap between the call for mass-scale decolonization and the dismantling of settler capitalism by exploring pathways which orient the land and Indigenous knowledge as relationships and core values mobilized towards a resurgence reality. Dechinta is herein conceived as a pathway movement of arming oneself with knowledge to fight the hierarchical scales of settler politics, a movement where collective and personal transformation through learning on the land is part and parcel of a strategy of resistance to settler capital, producing an alternative knowledge economy centered around the value of land as an infinite producer of health, knowledge, and sustainable, self-determining communities.

Read more about Dechinta on this database, or consult its website.

Access this Resource:

Read the full PDF on Decolonization online.

Ballantyne, Erin Freeland. “Dechinta Bush University: Mobilizing a knowledge economy of reciprocity, resurgence and decolonization.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, no. 3 (2014): 67-85.

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: