Great Bear Lake Indians: A historical demography and human ecology. Parts 1 & 2.

Morris’ work focuses on Fort Franklin (now Délı̨nę) in the Sahtú region. She splits the results of her research and thesis fieldwork into two primary historical segments (pre and post European contact). Her emphasis is primarily on population, human ecology and geography, and trends in seasonality, subsistence, migration, and other elements of history and social organization.

Access this Resource:

While Morris' two articles are available only as physical documents in several University libraries, a digital copy of the thesis they are based on is online from the University of Saskatchewan: http://hdl.handle.net/10388/etd-07032012-110232

Morris, Margaret W. “Great Bear Lake Indians: A historical demography and human ecology. Part 1: The situation prior to European contact.” Musk-Ox 11 (1972): 3-27.

"Part 2. The situation after European contact.” Musk-Ox 12 (1973): 58-80.

The Hare Indians: notes on their traditional culture and religion, past and present

Hultkrantz recounts an interview with a young man from Fort Good Hope, by the name of “Little Fox,” in the context of historical ethnographic literature. He concludes that the youth of Fort Good Hope are experiencing a resurgence of traditional values and attempting to preserve these where possible.

A response to this article and ensuing academic debate is described elsewhere in this catalogue.

Access this Resource:

Preview the article on Taylor and Francis online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.1973.9981071

Hultkrantz, Åke. “The Hare Indians: notes on their traditional culture and religion, past and present.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 38, 1-4 (1973): 113-152.

Great Bear Lake Indians: A Historical Demography and Human Ecology

Morris’ work focuses on Fort Franklin (now Délı̨nę) in the Sahtú region. Her paper gives an overview of “the changes in human ecology and demography of the Indians of Great Bear Lake from just prior to European contact to the late 1800’s,” (3) with an emphasis on population geography, i.e., the population traits and 'geographic personality’ of places. Her overview includes some valuable historic maps and climate records, along with descriptions of hunting practices, seasonal migration, subsistence, and traditional clothing and cooking. She also provides population estimates from the 19th and 20th centuries for the Great Bear Lake and Fort Good Hope regions.

Abstract:

Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories is the largest lake located entirely within the bounds of Canada. Today there are two small settlements along its shores: the small mining town of Port Radium on McTavish Arm inhabited by non-Indians, and the small Indian settlement of Fort Franklin on Keith Arm. This study is concerned with the Indians of Fort Franklin and district. Fort Franklin is located four miles from where Bear River begins to flow down to the Mackenzie River. It is approximately 90 miles from Fort Norman, the closest community, 120 miles from Norman Wells, and about 400 miles from either Yellowknife or Inuvik (Fig. 1). Its inhabitants in July 1969 comprised 368 Indians (339 Treaty, 29 non-Treaty) and 37 transient whites, mainly government, church or trading officials (Pers. comm. Fr. Denis, 1969). Most of the Indians are fur trappers who live in the "bush" around the lake for three to four months every winter setting up and operating their trap-lines. Their income is supplemented by a spring beaver hunt, by guiding at the tourist fishing lodges located around the lake, or by working with the transportation companies during the summer months. A few are employed either part or full time with the government or Hudson's Bay Company. The Great Bear Co-operative provides an outlet for local handicraft. Social welfare and other government allowances form an increasing proportion of the total income (Pers. comm. W. English, Area Administrator, 1969). Since the erection of about eighteen log houses in the early 1900's, Fort Franklin has had a number of Indians residing in the settlement on a year round basis. With the discovery of pitchblende, silver, and other minerals at Port Radium and petroleum at Norman Wells in the 1920's, Great Bear Lake and River became important as a commercial transportation route. Oil, food, and equipment were barged upstream, and silver-copper concentrates downstream to Fort McMurray, and then by rail to the smelter at Tacoma, Washington. Later, radium was sent to Port Hope, Ontario, for refining at Eldorado (Eldorado, 1967, pp. 18-21). Following upon the establishment of a permanent Roman Catholic Mission, Federal Day School, and Hudson's Bay Company post in 1949-50, the Indians settled in Fort Franklin, and since that time, their numbers have more than doubled. Prior to 1900, these Indians were quasi-nomadic and lived in camps around Great Bear Lake. Once, their forefathers had been nomadic hunters, pursuing the migratory Barren Ground caribou, and subsisting on fish, hares, and other animals in abundant supply. But during the century and a half of European contact these Indians underwent many changes. Most significantly, they decreased in number and gradually became settlement-orientated. The old life of the "bush" and caribou was forever gone.

Access this Resource:

A digital copy of this thesis is available online from the University of Saskatchewan: http://hdl.handle.net/10388/etd-07032012-110232

Morris, Miggs. Great Bear Lake Indians: A Historical Demography and Human Ecology. Master’s Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1972.

The Ethnography of the Great Bear Lake Indians

Osgood drafted this text as a monograph based on 14 months of fieldwork from 1928 to 1929, for the National Museum of Canada. This detailed text includes notes on the history, ways of life, materials, arts, social organization, and faith of peoples around Great Bear Lake (including, in his terms, the Sahtudenes, the Dogribs, Hares, Slaves, Yellowknifes, and Mountain Nations). It also contains some pertinent details about health, waves of influenza, and the relationships between visitors and Indigenous peoples.

Read more about Cornelius Osgood's work:

The Distribution of the Northern Athapaskan Indians

An Ethnographical Map of Great Bear Lake

Access this Resource:

Search within the text (no full preview available) on Google Books.

Osgood, Cornelius. “The Ethnography of the Great Bear Lake Indians.” In Annual report for 1931: National Museum of Canada Bulletin 70 (1932): 31-97.

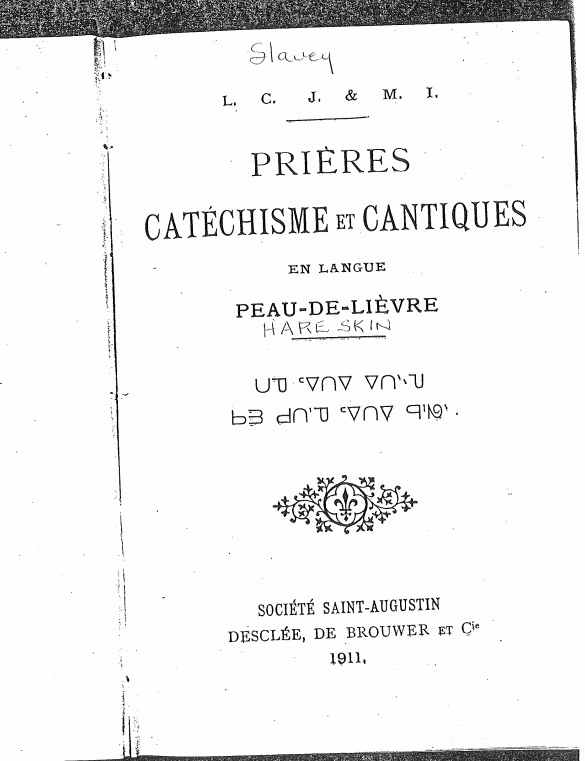

Prières Catchésme et Cantiques en Langue Peau-De-Lièvre [Hareskin Syllabics]

This scanned document is a French guide to “Peau-De-Lièvre” (Dene/"Hareskin") syllabics. The devotional translations were contributed to by Audemard, Henri, 1864-1948; Ducot, Xavier, 1848-1916; Gouy, Édouard, 1869-1943; Petitot, Émile, 1838-1917; and Séguin, Jean, 1833-1902. Petitot wrote a significant body of work about his time in the Sahtú region - search his name in this database to find more of his writings.

Access this Resource:

Read the full text online.

Prières Catchésme et Cantiques en Langue Peau-De-Lièvre [Hareskin Syllabics]. Société Saint-Augustin, Desclée, De Brouwer. 1911.

Dictionnaire de la langue Dènè-Dindjié, dialects Montagnais our Chippewayan, Peaux de lièvre et loucheux, etc.

This was the first extensive dictionary of northern Athapaskan languages, and it includes Sahtú varieties. Émile-Fortuné Petitot was a French oblate missionary, who worked in the Athabasca-Mackenzie area of what is now the Northwest Territories during 1862-1883. There is also a version published in San Francisco by A.L. Bancroft (also 1876).

Access this Resource:

Petitot, Émile. Dictionnaire de la langue Dènè-Dindjié, dialects Montagnais our Chippewayan, Peaux de lièvre et loucheux, etc. Paris: E. Leroux, San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft, 1876.

Read the full text online from the Internet Archive:

Phone: 867-374-4040

Phone: 867-374-4040 Email:

Email: